Introduction

Diaphragmatic hernias represent a significant surgical challenge, particularly when they are large, contain multiple organs, and result from previous trauma. These uncommon conditions occur when abdominal contents herniate into the thoracic cavity through a defect in the diaphragm, potentially compromising both respiratory and digestive functions. While congenital forms like Bochdalek and Morgagni hernias are well-recognized, traumatic diaphragmatic hernias (TDH) are less common and may present with delayed symptoms years after the initial injury.

This case study explores the successful surgical management of a complex post-traumatic diaphragmatic hernia at Burjeel Hospital in Sharjah, highlighting the multidisciplinary approach required to address this challenging condition. The case is particularly notable for the large size of the defect, the extensive organ herniation, and the rare associated finding of absent pericardium.

Understanding Traumatic Diaphragmatic Hernias

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Traumatic diaphragmatic injuries occur in approximately 0.8-8% of patients with blunt thoracoabdominal trauma, most commonly from motor vehicle accidents. The injury typically results from sudden increases in intra-abdominal pressure during trauma, causing the diaphragm to rupture at its weakest points. Left-sided ruptures are more common (approximately 75% of cases) due to the protective effect of the liver on the right hemidiaphragm.

The natural history of undiagnosed diaphragmatic injuries often follows three distinct phases:

- Acute phase: Immediately following injury, marked by respiratory distress and other trauma-related symptoms

- Latent phase: A period of minimal or absent symptoms that may last for months to years

- Obstructive or strangulation phase: When herniated abdominal contents become incarcerated or strangulated, leading to acute symptoms

The progressive nature of these hernias results from the pressure gradient between the abdominal and thoracic cavities, which gradually enlarges the defect and promotes herniation of abdominal contents into the thorax.

Clinical Implications

Untreated diaphragmatic hernias can lead to serious complications:

- Respiratory compromise: Due to compression of lung tissue and mediastinal shift

- Gastrointestinal obstruction: When herniated bowel becomes obstructed

- Strangulation: Compromised blood supply to herniated organs

- Pleural effusion: Accumulation of fluid in the pleural space

- Cardiac dysfunction: From compression or displacement of the heart

Early diagnosis and surgical repair are essential to prevent these potentially life-threatening complications.

Case Presentation

Patient Profile

A 29-year-old male presented to Burjeel Hospital in Sharjah with complaints of abdominal pain and difficulty breathing that significantly affected his daily activities. These symptoms had persisted for approximately two years without improvement, despite various treatments. Notably, the patient reported a history of blunt trauma to the chest and abdomen from a motor vehicle accident, which had occurred prior to the onset of his symptoms.

Clinical Presentation

The patient described progressive shortness of breath, particularly with exertion, and intermittent abdominal discomfort. Physical examination revealed decreased breath sounds over the left hemithorax and abdominal tenderness, raising suspicion for a thoracoabdominal pathology.

Diagnostic Workup

Initial investigations included:

- Chest X-ray: Revealed elevation of the left hemidiaphragm with abnormal gas shadows in the left thoracic cavity

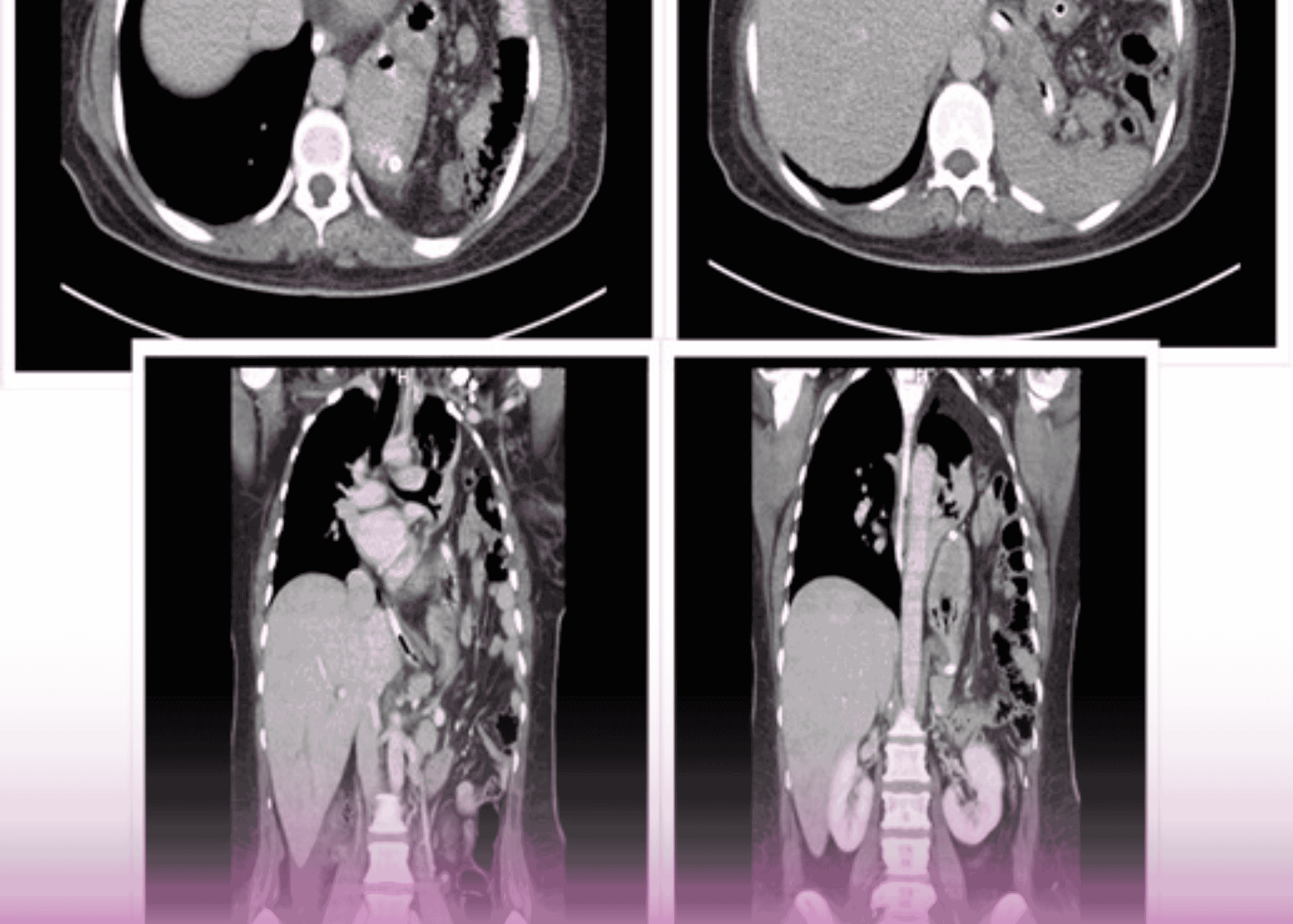

- CT scan of the abdomen and chest: Demonstrated a large defect in the left hemidiaphragm with herniation of multiple abdominal organs into the left thoracic cavity, including:

- Spleen

- Stomach

- Large portions of the colon

- Additional findings: The CT scan also showed significant atelectasis (collapse) of the left lung due to compression by the herniated abdominal contents

Based on these findings and the patient’s history of trauma, a diagnosis of post-traumatic diaphragmatic hernia was established.

Surgical Management

Preoperative Planning

After thorough discussion of the case with the patient and his family, the decision was made to proceed with surgical repair. Given the complexity of the case, a multidisciplinary surgical team was assembled, including:

- General surgeons

- Thoracic surgeons

- Anesthesiologists

The surgical approach was carefully planned, taking into consideration the chronicity of the hernia, the size of the defect, and the multiple organs involved.

Surgical Approach

The surgical team, led by Dr. Mohamed Eraki , Consultant of General and Laparoscopic Surgery, Dr. Imtiaz Ahmed and Dr. Taj Mohamed, Consultant Thorax Surgeons, opted for a combined thoracoabdominal approach to ensure optimal exposure and management of both abdominal and thoracic components of the hernia.

The procedure consisted of:

- Initial abdominal laparotomy: To access the abdominal cavity and assess the condition of the herniated organs

- Left lateral thoracotomy: To provide direct access to the diaphragmatic defect and thoracic cavity

- Comprehensive exploration: Of both cavities to identify all anatomical abnormalities

Intraoperative Findings

The surgery revealed several significant findings:

- Large diaphragmatic defect: Confirming the preoperative imaging

- Extensive herniation: The spleen, stomach, and large portions of the colon were found within the left thoracic cavity

- Redundant diaphragm: The remaining diaphragmatic tissue was abnormally loose and stretched

- Absent pericardium: A rare associated congenital anomaly was discovered, with absence of the pericardial sac

- Compressed left lung: The lung was significantly atelectatic but otherwise viable

Surgical Technique

The surgical team performed several key steps:

- Organ reduction: Carefully reducing the herniated abdominal organs (spleen, stomach, and colon) back into the abdominal cavity

- Assessment of viability: All herniated organs were thoroughly examined and found to be viable with no signs of ischemia or strangulation

- Diaphragmatic repair: Multiple rows of plication (folding and suturing) of the redundant diaphragm were performed from both the thoracic and abdominal approaches

- Chest drainage: Placement of thoracic drains to evacuate air and fluid

- Layered closure: Of both the thoracotomy and laparotomy incisions

Postoperative Care

Following the procedure, the patient was transferred to the Intensive Care Unit for close monitoring. Key aspects of postoperative management included:

- Respiratory support and monitoring

- Pain management

- Early mobilization

- Gradual resumption of oral intake

The patient’s recovery was uneventful, with progressive improvement in respiratory function and resolution of abdominal symptoms. After an appropriate period of monitoring, the patient was discharged from the hospital in good health.

Discussion

Surgical Considerations

This case highlights several important surgical considerations in the management of complex diaphragmatic hernias:

1. Approach Selection

The choice of surgical approach is critical in complex diaphragmatic hernias:

- Transthoracic approach: Provides excellent exposure of the diaphragm and thoracic cavity, allowing direct visualization of the hernia and any adhesions to thoracic structures

- Transabdominal approach: Offers better access to abdominal organs and facilitates their reduction and assessment

- Combined approach: As used in this case, provides comprehensive access to both cavities in complex cases

For large, chronic hernias with multiple herniated organs, the combined approach offers significant advantages, despite increased surgical trauma.

2. Repair Technique

Several options exist for diaphragmatic reconstruction:

- Primary repair: Direct suturing of the defect, possible when there is sufficient healthy tissue

- Plication: Folding and suturing of redundant diaphragm to restore tension and function

- Mesh reinforcement: Use of prosthetic or biologic materials for large defects with insufficient tissue

- Muscle flap reconstruction: In cases of extensive tissue loss

In this case, the redundant nature of the diaphragm allowed for effective plication without the need for prosthetic materials, which minimizes the risk of infection and erosion into adjacent structures.

3. Management of Associated Anomalies

The finding of an absent pericardium in this case represents a rare association that required no specific intervention but demonstrates the importance of thorough intraoperative exploration and readiness to address unexpected findings.

Clinical Relevance

This case underscores several clinically relevant points:

1. Delayed Presentation

The two-year interval between the traumatic event and definitive diagnosis highlights the often indolent course of traumatic diaphragmatic injuries. Healthcare providers should maintain a high index of suspicion in patients with a history of thoracoabdominal trauma who present with respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms, even years after the initial injury.

2. Diagnostic Challenges

Diaphragmatic hernias can be challenging to diagnose, particularly when symptoms are nonspecific. CT imaging has emerged as the gold standard for diagnosis, providing detailed information about the defect size, location, and herniated contents.

3. Multidisciplinary Approach

The successful management of this complex case required collaboration between general surgeons, thoracic surgeons, and anesthesiologists. This multidisciplinary approach ensured comprehensive assessment and treatment of both thoracic and abdominal components of the hernia.

4. Long-term Outcomes

Complete resolution of the patient’s symptoms following surgical repair confirms that even long-standing diaphragmatic hernias can be successfully treated with appropriate surgical intervention. Early diagnosis and repair remain preferable to prevent complications, but even delayed repair can provide excellent outcomes.

Conclusion

This case illustrates the successful surgical management of a complex post-traumatic diaphragmatic hernia with multiple herniated organs and an associated congenital anomaly. Through a carefully planned combined thoracoabdominal approach, the surgical team at Burjeel Hospital in Sharjah was able to reduce the herniated contents, repair the diaphragmatic defect, and restore normal anatomy and function.

For clinicians, this case emphasizes the importance of maintaining awareness of diaphragmatic injuries in patients with a history of thoracoabdominal trauma, even when presentation is delayed. The case also highlights the value of advanced imaging in diagnosis and the benefits of a multidisciplinary surgical approach in complex cases.

For patients suffering from undiagnosed diaphragmatic hernias, this case offers hope that even long-standing, complex hernias can be successfully treated with appropriate surgical intervention, resulting in significant improvement in symptoms and quality of life.